Search

What are the dimensions and indicators most commonly used by countries in their national MPIs?

In the following article, Diego Zavaleta presents the dimensions and indicators that the Latin American countries are using in the elaboration of their Indices of Multidimensional Poverty. It also identifies the main lessons that emerge from these experiences.

The creation of a multidimensional poverty measure implies a series of normative decisions regarding various aspects, including the dimensions, the indicators, the cut-off points, and the weights to be used. These decisions sound intimidating to many people. In the case of choosing dimensions, for example, people ask themselves questions that are not trivial: How to choose a group of dimensions that is wide enough to do justice to the complex reality of poverty and at the same time is concise enough to result in a meaningful measurement while avoiding the loss of data in a myriad of indicators? How to guarantee that no important topic is left out and, at the same time, highlight certain priorities? If we have already opened the discussion to include meaningful dimensions for our reality, how do we guarantee that relevant topics for which there is not much experience in how to measure them do not abound in the index at the expense of more traditional dimensions and extensively tested indicators?

These are certainly complex questions that require multiple pieces of information. What is the purpose of the measurement? What is the public consensus regarding what living in poverty means? What commitments has the State undertaken? What do the theory and the empirical evidence tell us? Decision making regarding these issues also faces a series of practical restrictions, such as political considerations, data restriction (do we have the data to measure what we want?), the budget or the capacity to carry out a survey which involves the desired topics.

In this magazine we will address several topics regarding the normative decisions over time. On this occasion, we would like to start by showing the dimensions and indicators that the countries are using and some lessons which these experiences teach us.

To begin with, it is important to mention that countries have been answering these initial questions in very different and less complicated ways than first anticipated. Colombia, for example, used already defined national priorities and an ample consultation with academics and experts on the subject to resolve them; Mexico, defined its dimensions and indicators as endorsed in its Constitution and in a Law supported by all political parties; Bhutan, Pakistan and El Salvador through participatory processes with people living in poverty, and Chile through a Presidential Committee formed by civil society representatives.

Countries have widened the way to evaluate poverty and have brought it closer to the way in which people understand this situation, maintaining a preference for extensively tested indicators

But, what specific dimensions and indicators are countries and international comparability initiatives using? The case of Latin America – the region of the world where these measures have been incorporated more quickly into official statistics – provides a solid example. In the last few years, a total of 7 countries in Latin America have made public official multidimensional poverty measurements and another 6 are actively working to develop them. There are also proposals for a regional index that allows for comparisons between countries, such as the proposal put forward by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). There is also the Global MPI published by OPHI and the UNDP’s Human Development Report. Tables 1 and 2 show the comparisons between the dimensions and indicators used by the various countries, which already have official measurements, as well as the indexes of global (Global MPI) and regional (ECLAC) comparability.

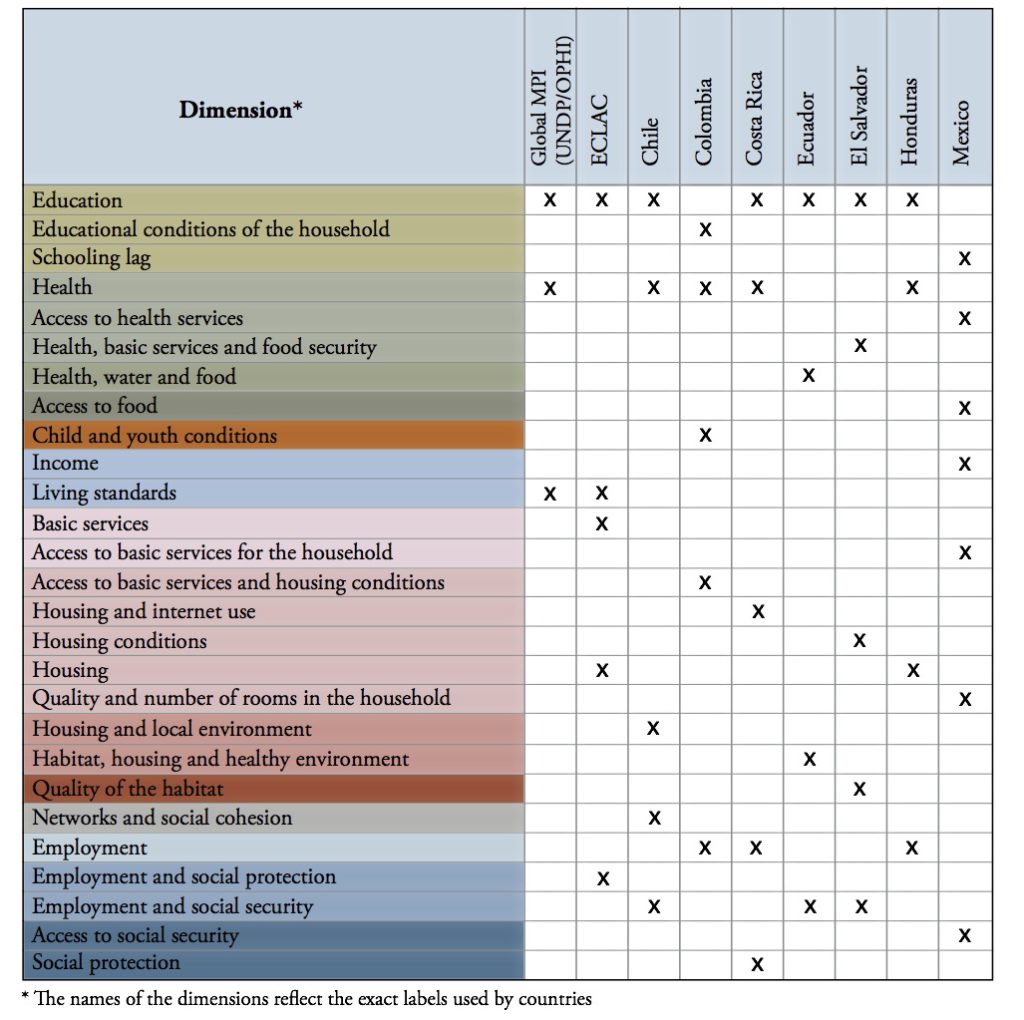

Table 1. Dimensions used in multidimensional poverty measures – Latin America and the Caribbean

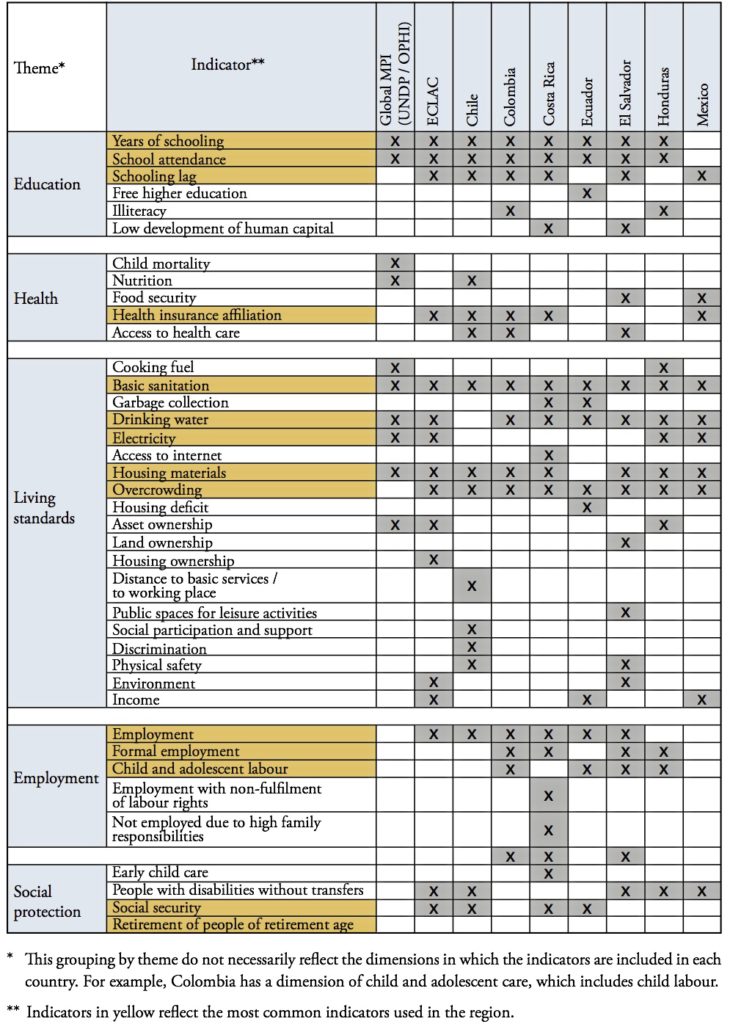

Table 2. Indicators used in multidimensional poverty measures – Latin America and the Caribbean

Tables 1 and 2 show several interesting aspects. The first is that thus far coincidence lot of overlap exists in the dimensions chosen by different countries and the initiatives to characterize poverty – that is, the total number of dimensions that underlie most indexes is relatively small (Table 1). Regardless of the specific name used (the exact names chosen by the countries to define their dimensions are used in Table 1), the discussion thus far has revolved around 10 large dimensional groups: education, health, childhood and adolescence, standard of living, housing, basic services, habitat or local environment, social networks and cohesion, employment, and social security. Except for “habitat or environment” (which involves an interesting array of aspects, such as the local environment, the neighbourhood or community’s infrastructure, or physical safety) these dimensions correspond to topics which have been treated as priorities for many years.

The second relevant aspect is that, although the number of indicators shows some diversity (39 indicators), quite a low number of them (the 14 in yellow on Table 2) represent a very high percentage of each national measurement. This shows that a large number of national measures use a reduced subgroup of indicators. Once again, the great majority of these are widely known.

Finally, amongst the rest of the indicators (not in yellow) there are many aspects that for years have been part of the set of indicators used to analyse development, such as infant mortality.

These results show an emerging pattern: countries have widened the way to evaluate poverty and have brought it closer to the way in which people understand this situation, maintaining a preference for extensively tested indicators. However, some innovation is also apparent, such as in the case of the incorporation of physical safety or environmental indicators (aspects which, by the way, are now recognised by the new Sustainable Development Goals). All this shows an essential trait of these indices: that they can be adapted to reflect specific contexts and incorporate aspects which people consider vital to understand poverty in accordance with their own reality.

* Translated from Spanish into English by Alicia Holliday, UN Volunteer. Revised by Ann Barham.