Search

Revealing Sri Lanka’s Multidimensional Poverty

How would you describe poverty in Sri Lanka in historical terms? And what was the relevance of implementing a National MPI and a Child MPI in this context?

The Department of Census and Statistics (DCS) has been measuring poverty using a monetary approach of consumption expenditure based on the Cost of Basic Needs (CBN) since 2002, using the information collected from the Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES).

The incidence of monetary poverty in Sri Lanka has declined since 2002 moving from 46.7% in 2002 to 14.3% in 2019, based on the poverty line which was rebased in 2012/13.

Despite the sharp decline at the national level, poverty pockets still exist across regions of the country. Monetary poverty is important, but it is not accurate because it is unable to capture poor people’s experiences in other dimensions such as education, health, sanitation, access to drinking water, housing condition, among others.

Multidimensional poverty measures capture poor people’s deprivations experienced in different dimensions at the same time. They allow us to identify how many households and individuals are deprived and to analyse what the composition of their poverty is and how poverty differs between groups. This information can be used to inform an integrated policy framework to reduce poverty effectively and efficiently.

Poverty experienced by young children differs from poverty faced by adults. It can have different causes, and also different effects. Even short periods of deprivation faced by children, for instance in undernutrition and cognitive development, can permanently affect children’s long-term growth.

A focus on early childhood poverty is key to informing child poverty policies that can have long lasting effects on the development of the country’s human capital. Hence it is important to identify children’s deprivations and a child Multidimensional Poverty Index (CMPI) enables that.

Child poverty measures allow the identification of how many deprivations poor children face (also known as intensity) and provide information on the composition of poverty by age group and between girls and boys. This information can be used to increase awareness of child deprivation as a national priority.

The main challenge was to decide which indicator to include that responded to the country’s requirement to support policy.

In 2020 the Department of Census and Statistics produced the national Multidimensional Poverty Index (NMPI) and the linked child Multidimensional Poverty Index (CMPI) considering children aged 0–4 years old for the first time using data collected from the 2019 Household Income and Expenditure Survey, in collaboration with the Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative (OPHI), UNICEF country office in Sri Lanka and European Union (EU).

The Sri Lanka MPI is one of the first MPIs in the world to link the measure of child poverty directly and fully with national poverty. Why did you link the measure and what are its policy implications?

The child MPI for children aged 0–4 includes the same indicators as the national MPI and adds a fourth dimension to cover undernutrition and early childhood development.

The individual child MPI, therefore, shows additional child-specific deprivations for girls and boys under the age of 5. This information identifies multidimensionally poor children who are simultaneously experiencing their household’s multidimensional deprivations and child-related deprivations.

This information is valuable for making anti-poverty policies that keep child poverty top of development agendas. In addition, the child MPI identifies poor children across different age cohorts and provides information on which indicators to prioritize for targeting policies.

How were both measurements created? How were dimensions, indicators and weights chosen for both measurements?

These two indices were created using the 2019 Household Income and Expenditure Survey data. To compile the child MPI, a new module was incorporated to the survey, with the main objective of collecting additional information specifically related to child poverty. The unit of identification for the national MPI was the household and the unit of analysis was individual.

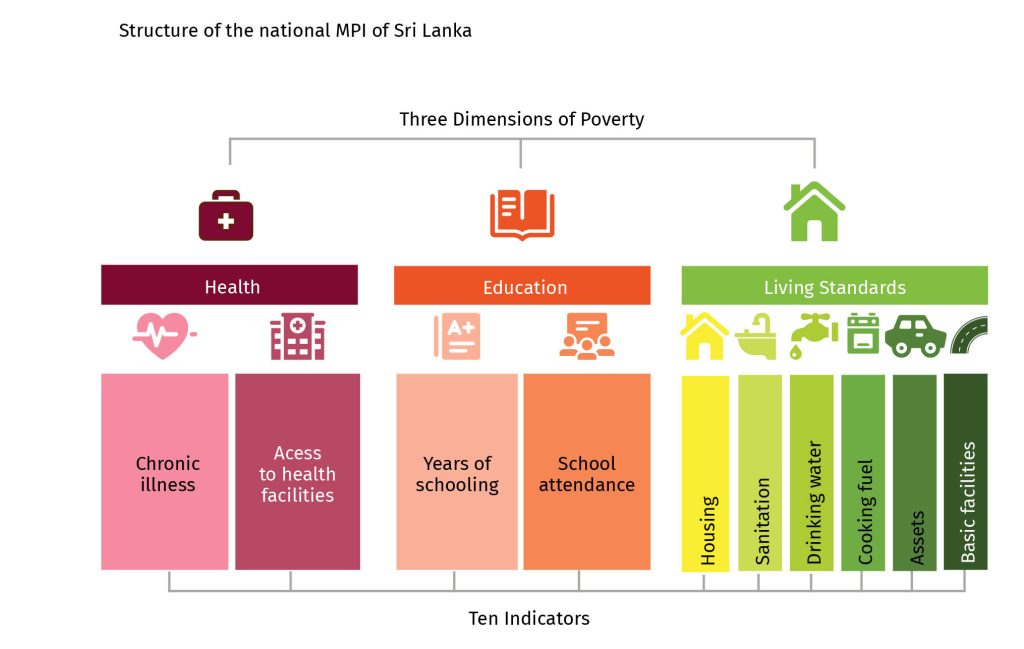

The national MPI in Sri Lanka has 10 indicators grouped into three dimensions.

What challenges did you face in making both measurements?

The main challenge was to decide which indicator to include that responded to the country’s requirement to support policy implications to target interventions for eradicating national and child poverty in Sri Lanka.

This challenge was addressed by arranging roundtable discussions and several stakeholders’ meetings. Then there were several discussions with stakeholders and technical partners to decide each indicator’s deprivation cut-off, the poverty cut-off and the weight of each of the indicator. A number of robustness analyses were conducted to decide the most appropriate deprivation and poverty cut-offs, as well as the weights.

This article was published in Dimensions 15