Search

Living in multidimensional poverty in India: Kari’s story

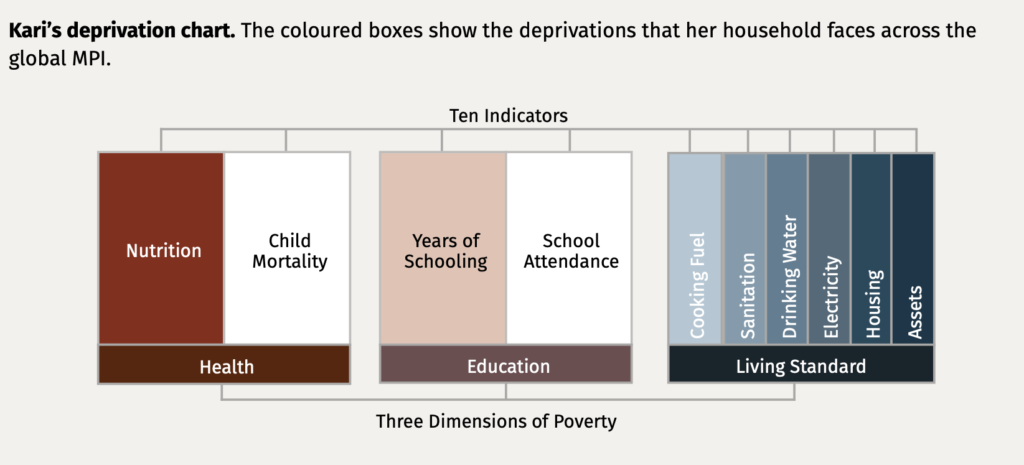

Kari is a 45-year-old woman who lives in her birthplace village in Bihar, India. She was married to her husband when she was 13, and they have a son and three daughters. The family is Hindu and belongs to the Musahar caste. During certain sea- sons, Kari finds agricultural employment related to the crop cycle, often walking 15 kilometres to work.

Over time, her left hand has become partially paralysed. Nonetheless, she strives to work as much as she can. She sows seeds and is occasionally employed by farmers to do weeding, for which she is paid INR 25 a day – much less than the prevailing wage due to her disability. During harvesting, she gathers the paddy and wheat crops. Being seasonal, harvesting work barely lasts for more than four weeks per year. She is paid in kind and can keep one-ninth of the produce that she helps to harvest. Overall, Kari works for less than two months annually, with no guarantee of daily employment. Her husband works half the year in Punjab, and their children have left home. Although proud of their children, Kari and her husband regret being unable to educate any of them due to needing ‘all hands on board’.

Kari wakes at 5 am every day, washes at the side of the road, sweeps the house, and then collects firewood for household fuel. An activist, she is also a member of a federation of four women’s self-help groups. Boasting over 100 members, they are known for engaging local officials and political leaders on a range of issues affect- ing the villages. Kari realizes that she is living through interesting times. For years, women like her were stigmatised. Today, thanks to a series of affirmative action steps taken by the Bihar state government, they can access various government schemes. Yet Kari’s house- hold is still poor according to the Indian government’s Below Poverty Line survey instrument and the MPI.

This article was published in Dimensions 9.