Search

Are Changes in the Incidence of Multidimensional Poverty and Monetary Poverty Similar?

For many years it was argued that, for someone experiencing poverty, an increase in income would almost automatically have a positive trickle-down effect on other aspects of their life. If this were the case, one would expect changes in levels of monetary poverty within a country to correlate with the results given by other means of measuring poverty. But how do changes in multidimensional poverty really compare to changes in monetary poverty? The answer varies from country to country.

Based on data from 27 countries that have reduced their levels of multidimensional poverty, it can be concluded that there is no consistent pattern between changes in the incidence of multidimensional and monetary poverty.

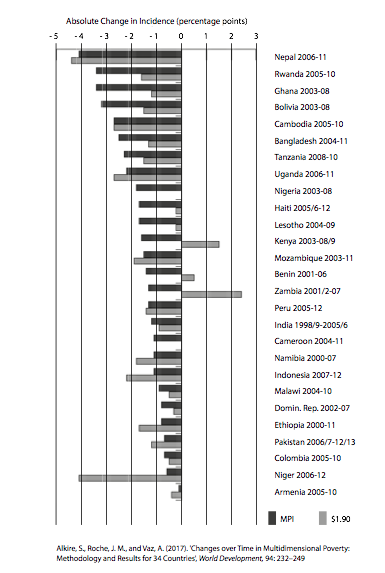

The graph below demonstrates that figures for the incidence of multidimensional and monetary poverty can vary significantly in their rates of change – and even in the direction of that change. For instance, countries like Rwanda, Ghana, Bolivia, Nigeria, Haiti, and Lesotho reduced the incidence of multidimensional poverty much faster than the incidence of poverty based on US$1.90/day. The opposite occurred in countries like Niger, Indonesia, and Namibia.

For their part, Kenya, Benin, and Zambia managed to reduce multidimensional poverty despite registering increases in terms of monetary poverty.

These results demonstrate the relevance of complementing monetary measurements with multidimensional measurement. If progress were measured only in terms of a reduction in monetary poverty, Nepal, Niger, Cambodia, Uganda, and Indonesia, in that order, would be considered leaders in the reduction of poverty, and the huge advances made in Rwanda, Ghana, and Bolivia would be invisible.

Photo: Alex Berger.