Search

Child Indicators for MPIs

Multidimensional Poverty Indices (MPIs) are based on household survey data which provide information on the multiple deprivations experienced by households and individuals.

Unfortunately, gaps in household survey data remain a major constraint for MPI construction. Among other issues, key indicators that capture the breadth and depth of deprivations experienced by children are often missing.

In a recent curation exercise, we selected a small set of strong, tested and validated child indicators with the potential to be used for MPI design in middle and high-income countries (MICS/HICS).

The curation was based on an extensive review of existing survey modules and MPI applications.

A detailed background paper was prepared for the workshop on ‘Improving the Collection and Availability of Multidimensional Poverty and Wellbeing Data’ which took place in Oxford in early 2024. In this article, I will summarise the key lessons learned.

Why do child-specific indicators matter?

Many reasons support the rationale to include child-specific indicators in MPI measures.

• Future opportunities in life: Childhood deprivations have a detrimental impact on their capabilities later in life, perpetuating a vicious cycle of poverty. In turn, at the country level, low human capital becomes a barrier to economic development and other development outcomes.

• Child wellbeing perspective: Child indicators reflect the specificity of children’s wellbeing, including issues which would be overlooked if only adult or household level indicators were included in a multidimensional measure.

• Children’s rights: Child poverty is a violation of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UN–CRC). Child indicators allow for the monitoring of children’s rights.

• A perspective on life cycle stages: When choosing indicators, it is important to consider the life cycle stages of childhood, including perinatal, neonatal, infancy, preschool-age, school-age, and adolescence. Deprivations manifest in different ways according to each life cycle stage. Child-specific indicators aim to capture this diversity.

What are the existing child indicators in national MPIs?

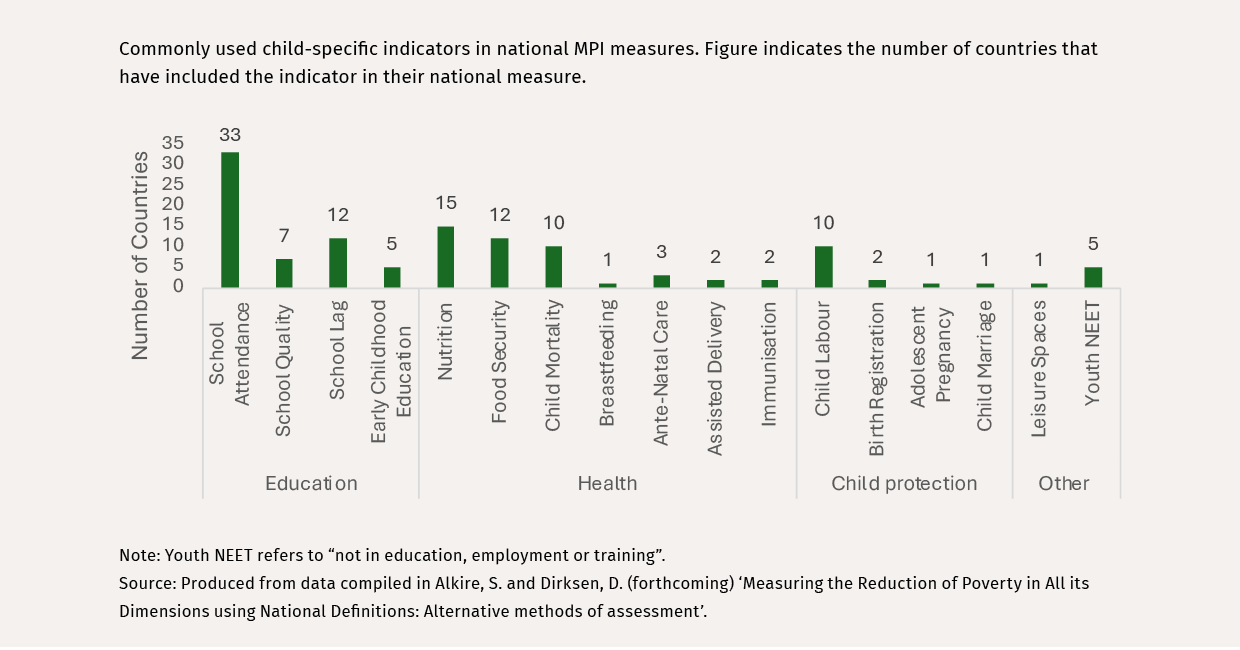

A wide range of child-specific indicators have been included in existing national MPIs. The six most common child indicators are school attendance (33 countries), nutrition (15 countries), school lag (12 countries), food security (12 countries), child mortality (10 countries), and child labour (10 countries). The inclusion of these indicators is often limited to data availability, as in the case of nutrition and child mortality, which are not always collected and so are often missing in MPI measures.

There are additional indicators which appear in other child-specific MPIs (Bhutan, Bangladesh, Nigeria, Panama, Thailand, and Sri Lanka), or in the Arab regional MPI. These include whether children live with their parents or not, investment in cognitive development, breast-feeding, child security, teenage pregnancy, or female genital mutilation.

A UNICEF study on child poverty in Europe also includes: access to clothing and shoes, books at home, games (indoor/outdoor), social activities, ownership of a computer or mobile phone and access to internet. Eurostat uses the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) data to produce child indicators on basic needs and unmet needs for medical examination or treatment, albeit only every three years.

What challenges remain?

Gaps in available survey data remain the main challenge, not least because national MPIs are often based on existing national household surveys designed for other purposes. While surveys may contain some child indicators, blind spots remain for some age groups. For example, surveys may include data on school attendance for school-age children but miss early childhood education which is key for children’s cognitive and psychosocial development. Some health or nutrition indicators may be available for under five children, but surveys often lack data on health status for older children.

Multi-topic household surveys do not yet typically include short sets of questions that focus on the extent of child development. While it is easier to measure school attendance, more effort is needed to measure learning such as reading or numerical abilities, or cognitive development in early childhood.

Survey programmes, including UNICEF-MICS, the Young Lives Project and EU-SILC, are deeply investing in testing and validating questions to better measure some of these missing topics. Promising examples include the Early Childhood Development Index 2030 and the revised discipline module for UNICEF-MICS7.

Validated survey modules often exist, but they have only been implemented and tested in limited contexts. This is the case with the very promising indicators developed by the EU–SILC, such as the living standards and material deprivations scale.

Further validation is needed to ensure the modules are reliable in other continents or countries with different levels of development and cultural variations.

Indicators that are relevant to some contexts may not work elsewhere, where the occurrence of such deprivations is too rare. For example, child marriage is rare in HICS, but adolescent pregnancy remains an area of concern. Similarly, coverage of vaccination may be nearly total in a country, but other health deprivations may remain a problem among children and adolescents.

When choosing child indicators, it is important to check who responds to the questionnaire and whether this would produce additional undesired bias. For example, if adults report answers to health status questions or discipline questions on behalf of the child, the results may not provide accurate information.

The reference period is also sensitive in MPI measures. A week or 24 hours’ recall is often used to ensure the respondents remember and report accurately. But short reference periods are problematic for MPI metrics which aim to monitor poverty over longer periods, and normally provide an annual estimate.

Ultimately, the normative reasons for including child indicators need to be observed carefully. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child as well as the SDG measurement framework provide a good framework for this.

A set of child indicators and survey questions

The education feature in this Dimensions issue proposes the inclusion of three key child indicators that we agree are very relevant. These include a refined indicator on school attendance, including questions about the reasons for school absenteeism, and more importantly a measure of the quality of primary education. In addition to these, we also recommend measuring access to pre-primary education, by including a similar set of questions to those used by the EU-SILC to measure early childhood education.

A range of research, including evidence reviewed by the Young Lives project, stresses the importance of pre-school education for cognitive and psychosocial development which reduces inequalities later in life.

To complement indicators on child mortality and malnutrition (covered in the health and nutrition dimension), we propose including two indicators also frequently used by EU-SILC. This includes a short set of three questions to measure unmet needs for medical examination or treatment, which can be applied to both medical and dental care. A short set of one to three questions are also proposed to measured health status and chronic illness.

The dimension of child protection is often missing in multi–topic household surveys, except those focusing on children such as UNICEF-MICS. The normative reasons to include such indicators are rooted in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, and indeed, are included as core indicators in the SDG measurement framework.

Our proposal is to include a short set of questions from the MICS survey and International Labour Organization (ILO) guidelines to measure:

• Child labour (1 to 11 questions, depending on the precision on the measure)

• Child marriage and early union (3 to 7 questions)

• Adolescent pregnancy (1 to 4 questions)

• Childbirth and birth registration (2 questions)

Finally, we propose a set of indicators related to children’s living standards, including the EU-SILC living standards and material deprivations scale (1 questions with 13 items), and the commonly used Youth NEET indicator (2 to 20 questions depending on the level of precision).

The bottom line is a short module with 30 questions, or as many as 69 depending on the precision of the measurement. This will complement already existing information, adding nine child-specific indicators that are relevant to most middle- and high-income countries.

This article was published in Dimensions 16