Search

Child and Adolescent Poverty and Social Rights in Mexico: A Multidimensional Poverty Measurement Approach

One of the reasons it is so important to eradicate child and adolescent poverty is because of its consequences for a person’s present and future development. Poverty during childhood is more likely to be permanent, since its effects on health and physical and cognitive development are usually irreversible. The economic and social dependency of girls, boys and adolescents generates complex dynamics of vulnerability that require appropriate public policy strategies.

This article provides a brief diagnosis of child and adolescent poverty (affecting children under the age of 18) in Mexico, using the official poverty measurement methodology developed by the National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy (CONEVAL is its acronym in Spanish). This methodology is based on a multidimensional poverty perspective and adopts a human rights approach. One of its advantages is that it allows for the provision of disaggregated measurements, whether on a territorial level – for federal and municipal entities – or for priority groups, such as the child and adolescent population.

The possibility of monitoring child and adolescent poverty in Mexico has facilitated collaboration between CONEVAL and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Since 2009, these institutions have established a joint working strategy for the study of child poverty, which has enabled them to gain a better understanding of its characteristics and evolution over time, and to identify elements for the design of public policies. The collaboration between the two institutions has already resulted in four reports (in 2010, 2012, 2013 and 2016) evaluating the state of poverty and access to social rights by girls, boys and adolescents in Mexico.

Background

The obligation to guarantee the full exercise of children’s rights is enshrined in various international and national treaties such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the General Law on the Rights of Girls, Boys and Adolescents (LGDNNA in Spanish) and the General Law on Social Development (LGDS in Spanish). The latter also establishes the functions of CONEVAL in the evaluation of social development policy and poverty measurement. With respect to this second objective, the law indicates that measurement should take into account family income, schooling lag, access to health services, social security, food and basic services in the household; the space and quality of the household, as well as the degree of social cohesion and access to paved roads.

The methodology for multidimensional poverty measurement responds to the human rights approach by incorporating the principles of universality (it focuses on people as universal rights-holders), interdependency (it considers the intrinsic intersection between social deprivations and social deprivations and income), indivisibility (it considers dimensions to be non-hierarchical and for social deprivation to exist when at least one right is violated) and progressiveness (it allows for the observation of gradual changes resulting from economic policies that have an impact on income or social interventions that improve access to rights). Thus, the methodology defines a person to be in a situation of poverty when she/he does not have enough income to acquire basic food and non-food goods and services, and when they lack access to at least one social right. In extreme poverty, income is insufficient to cover even basic food requirements and people demonstrate at least half of the social deprivations.

Child and adolescent poverty in Mexico

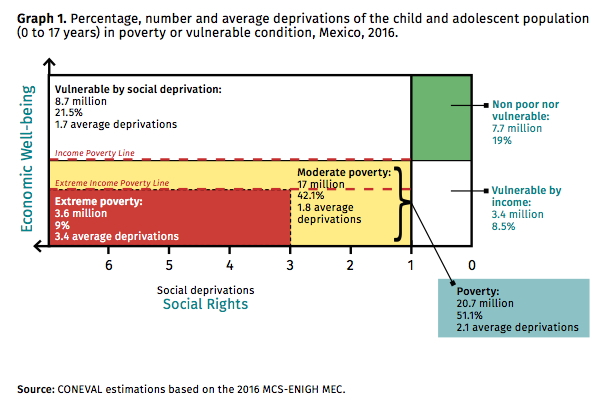

In 2016, half of the child and adolescent population in Mexico lived in poverty, 9% lived in extreme poverty and only one in every five children under the age of 18 did not experience economic or social deprivations.

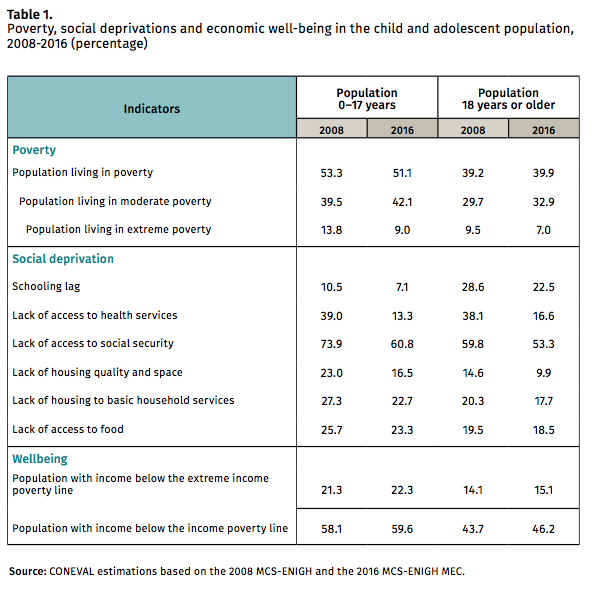

Poverty levels on a national scale saw practically no change between 2008 (44.4%) and 2016 (43.6%), but extreme poverty declined continuously. This trend is also evident among the child and adolescent population: extreme poverty dropped by more than 30% during this period.

This decrease has been possible thanks to the reduction of social deprivations, especially access to health services. This deprivation decreased by a third of its initial level among the child and adolescent population (from 39% to 13%). Lack of access to social security is the highest deprivation among the general population and is even more common among minors, indicating that adults do not have access to protection mechanisms that can be extended to their children. This leaves children exposed to age-related risks such as accidents, diseases and perinatal complications, among others.

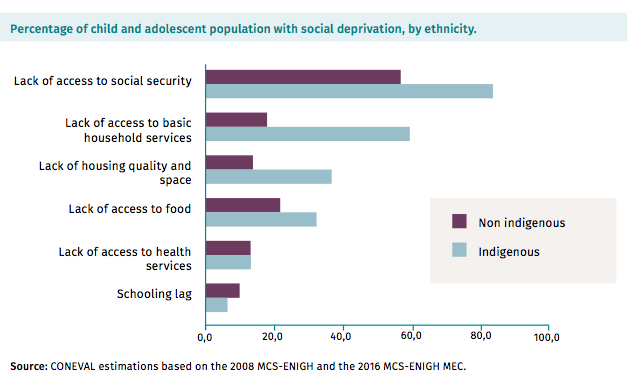

The indigenous child and adolescent population presents higher levels of social deprivation compared to those of the non-indigenous population (78.5% and 47.8%).

The difficulties with consistently increasing the income of the population have been the main obstacle to the sustained reduction of poverty in Mexico, a situation which is more critical among the child and adolescent population. Even though minors do not usually receive income directly, they belong to young and large families with fewer economic providers and more dependants. Additionally, from an early age the demands of family life present inherent difficulties that are exacerbated by the precarious integration of young adults into the job market and the absence of universal social protection mechanisms.

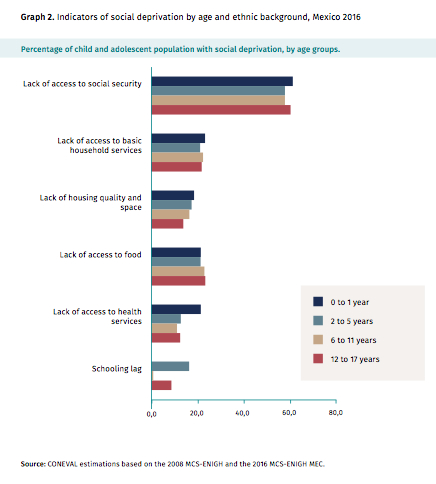

Child and adolescent poverty is not at all homogeneous. Early childhood, for example, is a phase of particular vulnerability: when children are younger, the housing they live in is of a lower quality and their lack of access to health services increases. As childhood progresses and homes are consolidated, other deprivations such as food insecurity and educational lag are accentuated, affecting the minors’ future development.

Furthermore, some attributes like ethnic background are linked to scenarios of discrimination that maintain certain populations in a situation of historical underdevelopment. The indigenous child and adolescent population presents higher levels of social deprivation compared to those of the non-indigenous population (78.5% and 47.8%). With the exception of access to health services, whose coverage shows significant advances in predominantly indigenous areas, children in these groups are exposed to deprivations that result in the violation of their fundamental rights.

Recommendations

Child and adolescent poverty has two distinctive features: children’s dependency on the living conditions of the adults in charge of their care and its prolonged effect throughout their lifetime.

Although the specificity of poverty at this age could benefit from the design and incorporation of child-specific poverty indicators, we believe that differentiated measurements would increase the risk of fragmenting social policy actions and diluting their effects. Furthermore, in the case of the child population, their well-being clearly depends largely, although not exclusively, on the well-being of the adults that care for them.

Interrupting the intergenerational reproduction of poverty should be central to the design of public policies for children and adolescents. Breaking this cycle requires actions that substantively improve families’ income and promote its fair distribution within households, benefiting the equitable development of minors. It is also important that all government and ministry orders are carried out in a coordinated way, improving the accessibility and quality of basic services in early infancy, childhood and adolescence.

It is essential to recognise the additional vulnerability experienced by minors belonging to populations that suffer from discrimination (such as rural and indigenous populations) and whose structural precariousness has led to underdevelopment in their infancy. It is necessary to work on strengthening protection mechanisms against all forms of violence, discrimination and exploitation that undermines the fundamental rights of children and adolescents. Although these problems are not exclusive to poverty, it does exacerbate them, leaving girls, boys and adolescents in a state of severe defencelessness.

* Gonzalo Hernández Licona, Former executive secretary of the National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy (CONEVAL). Ricardo Aparicio, Deputy general director for poverty analysis at CONEVAL. Paloma Villagómez, Deputy general director of guidelines for measuring poverty and social development at CONEVAL.

Translation by Theodora Bradford