Search

The Hidden Dimensions of Poverty

It is widely recognised that poverty is multidimensional and OPHI has played a prominent role towards this recognition. However, these dimensions need to be better specified and some have gone unrecognized. OPHI has identified five Missing Dimensions of poverty that deprived people cite as important in their experiences of poverty and that have been largely overlooked in large-scale quantitative work on poverty and human development: Informal and unsafe work; Disempowerment; Shame, humiliation and isolation; Physical insecurity, and Subjective ill-being. Survey modules have been developed to collect data on these dimensions. See Missing Dimensions of Poverty | OPHI.

To improve the global understanding of multidimensional poverty, the International Movement ATD Fourth World, together with researchers from the University of Oxford, launched in 2016 an international participatory research project to identify the key dimensions of poverty and their relationships.

This research has involved teams in Bangladesh, Bolivia, France, Tanzania, the United Kingdom and the United States. People with direct experience of poverty, academics and practitioners worked as co-researchers in national research teams.

The research process termed Merging of Knowledge (Merging Knowledge – Understanding It – ATD Fourth World (atd-fourthworld.org) has made possible a transformation in thinking at individual, community and national levels through the generation and sharing of knowledge. At Dimensions of Poverty Research – ATD Fourth World (atd-fourthworld.org) the international research report can be downloaded in five different languages. Five national research reports can also be downloaded and a 28-minute video on the research can be viewed in three languages.

By reaching out to listen to hundreds of people who are experiencing poverty, we have combined this knowledge with that of academics and practitioners through a process of multiple discussions in which the knowledge held by each group has been collectively challenged and evaluated. The result of each national process is a set of dimensions defining poverty in each country, as required by the Sustainable Development Goal 1.2.

Comparing the six country sets of dimensions through face-to-face discussions involving representatives of the national research teams, it became apparent that many dimensions were local manifestations for the same underlying attributes of poverty.

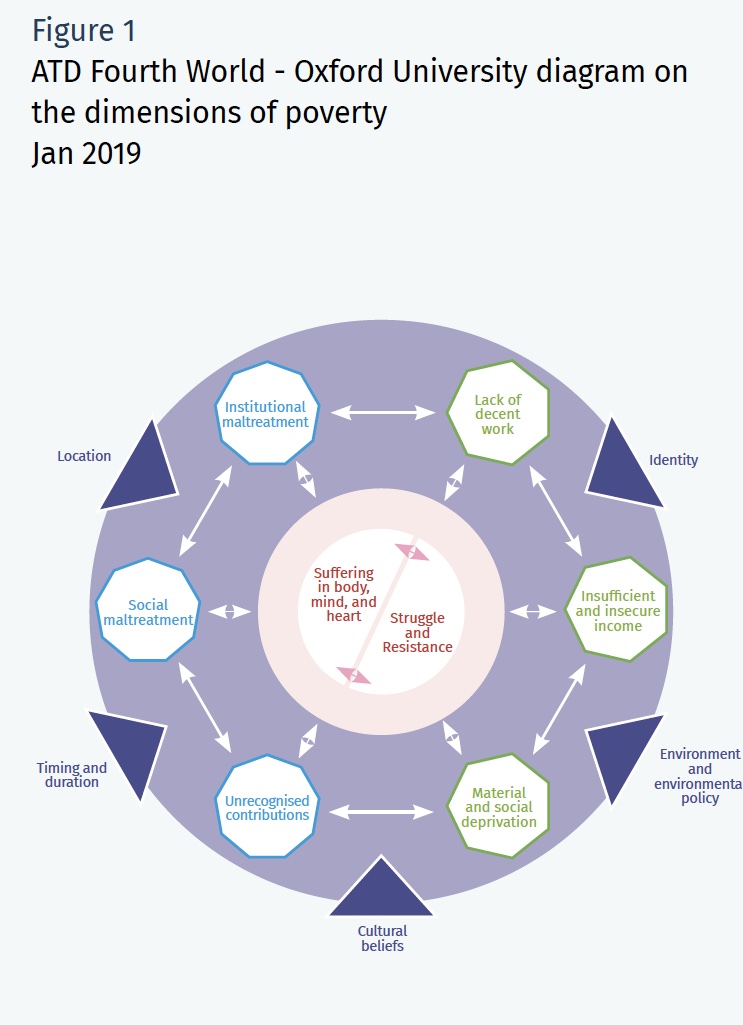

Therefore, we conclude that the complexity of poverty is best described in terms of three inter-related sets of dimensions as portrayed in Figure 1.

Six of these dimensions were previously hidden or rarely considered in policy discussions. Existing alongside the more familiar deprivations relating to lack of decent work, insufficient and insecure income and material and social deprivation, three dimensions are relational. These draw attention to the way that people who are not confronting poverty affect the lives of those who are: social maltreatment; institutional maltreatment and unrecognised contributions.

The three dimensions that constitute the core experience of poverty place the anguish and agency of people at the centre of the conceptualisation of poverty: suffering in body, mind and heart, disempowerment, and struggle and resistance. These dimensions remind us why poverty must be eradicated.

The nine dimensions, and hence the experience of poverty, are further understood to be modified by five factors.

Set 1: Core experience of poverty

Disempowerment: This is a lack of control and dependency on others resulting from severely constrained choices.

Suffering in body, mind, and heart: Living in poverty means experiencing intense physical, mental and emotional suffering accompanied by a sense of powerlessness to do anything about it.

Struggle and Resistance: There is an ongoing struggle to survive, which includes resisting and counteracting the effects of the many forms of suffering brought by privations, abuse, and lack of recognition.

Set 2: Relational Dynamics

Institutional maltreatment: This is the failure of national and international institutions, through their actions or inaction, to respond appropriately and respectfully to the needs and circumstances of people in poverty, and thereby to ignore, humiliate and harm them.

Social maltreatment: This describes the way that people in poverty are negatively perceived and treated badly by other individuals and informal groups.

Unrecognised contributions: The knowledge and skills of people living in poverty are rarely seen, acknowledged or valued. Often, individually and collectively, people experiencing poverty are wrongly presumed to be incompetent.

The Hidden Dimensions of Poverty research was deliberately carried out in a very participatory way with three developing and three developed countries, since all of them are facing poverty within their borders.

Set 3: Deprivations

Lack of decent work: This refers to the prevalent experience of being denied access to work that is fairly paid, safe, secure, regulated, and dignified.

Insufficient and insecure income: This dimension refers to having too little income to be able to meet basic needs and social obligations, to keep harmony within the family and to enjoy good living conditions.

Material and social deprivation: This refers to a lack of access to goods and services (education, healthcare, proper housing etc.) necessary to live a decent life, participating fully in society.

While every dimension is evident in all countries and most contexts, each varies in form and degree according to five modifying factors:

» Location, urban, peri-urban, rural.

» Timing and duration, short spells differing from long spells, poverty experienced in childhood or in old age varying from that experienced in working age.

» Cultural beliefs, concerning for example, whether poverty is generally thought to be caused by structural factors or by personal failings.

» Identity with discrimination on grounds such as ethnicity, gender and sexual orientation adding to that associated with poverty.

» Environment and environmental policy, from climate change, soil degradation, pollution to inadequate public infrastructure.

Prospects

The Hidden Dimensions of Poverty research was deliberately carried out in a very participatory way with three developing and three developed countries, since all of them are facing poverty within their borders.

Although the daily lives of people in poverty in the global North and in the global South are in many ways different, the list of dimensions that participants identified with academics and practitioners were very similar, with some country-specific dimensions.

This similarity stems from the fact that we did not focus on material deprivations, but on the core experience of people who endure them. This led the OECD Secretary General, Angel Gurria, to state at the OECD – ATD Fourth World international conference on 10 May 2019 in Paris: ‘Now, for the first time, the ATD – Oxford University research places a bridge across this gulf in the measurement approaches between rich and poor countries’. Since then, the French NSO (Insee) has included new questions to measure Institutional Maltreatment in a national survey, whose outcomes will be published in 2022.

The five Missing Dimensions of poverty identified by OPHI in 2007 have similarities with the six Hidden Dimensions we identified. Having them recognised in the work on poverty and development, and incorporated into survey instruments, so that they can be integrated into poverty dashboards, or new MPIs, would shed a new light that could help improve grassroots action and policy-making.

Yet the biggest challenge remains to put the suffering, agency and creativity of impoverished people and communities, not their deprivations, at the centre of our thinking and actions in order to meet the SDG pledge of ‘eradicating poverty in all its forms and dimensions, including extreme poverty’.

This article was published in Dimensions 12