Search

Elina Scheja: ‘The global pandemic underscores the need for a multidimensional analysis of poverty’

Elina Scheja is Lead Economist at the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida), the Swedish government agency in charge of implementing development cooperation policies. On behalf of the parliament and government, Sida’s goal seeks to ‘enable people living in poverty and under oppression to improve their lives’. They ‘facilitate development that prioritises the most impoverished in the world with a vision to safeguard the rights of every individual and their opportunity to live a dignified life’.

Sida currently works bilaterally with 37 countries in areas including gender equality, environment and climate change, agriculture and food security, conflict, peace and security and humanitarian aid. A multidimensional approach to poverty is at the core of Sida’s work. In this interview, Elina Scheja explains the background and use of this framework.

What is the background of Sida’s approach to multidimensional poverty?

I think it would be fair to say that Sida has been ahead of the game when it comes to working with multidimensional poverty. We have been doing this since the sixties and it has been a part of Sida’s mission to have a broad understanding of poverty. But more recently, at the start of the Millennium, Sida formulated a paper on how we view poverty in its different dimensions. It was then called ‘Perspectives on Poverty’ and outlined a view of poverty that resembles the capability approach. It covered material wellbeing as a core but also included the capabilities and opportunities that shape one’s life and power and voice to choose on matters of fundamental importance to oneself. It was also during that time that the government formulated a new policy for global development that doesn’t only apply to the Swedish Development Cooperation, but applies to all policy areas in Sweden.

How have the SDGs enriched this multidimensional poverty framework?

Sweden is a strong believer in the Sustainable Development Goals. Our work is framed by them, and we strive to make a significant contribution to their achievement. At the same time, the SDGs together with other political and contextual changes have inspired us to update our own understanding of multidimensional poverty as different agendas came together to reformulate our thinking.

First, the SDGs came in 2015 from the international agenda. Second, around the same time, the government of Sweden introduced a new policy framework for development cooperation that provided a holistic framework for international cooperation, and third, the development context and the world around us had changed since the previous goals on poverty reduction were set. The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) of reducing poverty numbers by half had been achieved and surpassed, but what remained was a more complex perspective of people who had been left behind. This was a different kind of world that we needed to understand better, so there was a need for new approaches.

In this spirit, Sida undertook quite a comprehensive exercise in 2016 to redefine a new analytical framework for multidimensional poverty called ‘Dimensions of Poverty’ that was launched in 2017. It took us almost two years of discussion with our country offices and thematic departments before we landed on this definition.

And I think it was needed to have that kind of discussion so that the organisation could own the results. Sida’s new multidimensional poverty framework is our domestication of what we mean by the SDG’s first goal ‘end poverty in all its forms everywhere’.

Which are the dimensions of poverty in Sida’s framework?

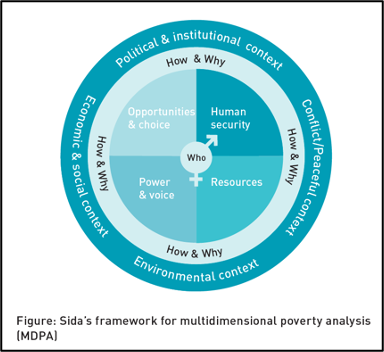

We recognise four dimensions of poverty. One is resources, which refers to something that is valuable and is invested in you. It has income but also educational achievement, health, and material and immaterial assets.

The second dimension is opportunities of choice, which is about your opportunity to build your resource base and use your resources to lift yourself out of poverty. It includes employment and opportunities to access social services, such as education.

The third dimension is power and voice, which means the ability to influence decisions that are of fundamental importance to your life. It is about anti-discrimination, and decision-making, not just in the political sphere but also in the community and in the household.

The fourth one is human security which refers to sexual, physical and psychological violence or threats of violence that would limit your opportunities to live a life in dignity. Adding human security to the other dimensions we had been working with was motivated by changes in the landscape of what poverty looks like.

There is more poverty concentrated in fragile and conflict contexts, so it was considered that this aspect of poverty was not really well captured in the other dimensions.

Sida has been restructuring our development financing in light of our understanding of how COVID-19 impacts people living in poverty including the ‘new poor’ that risk falling into poverty, and allowing our partners to flexibly adjust to the needs on site.

The main questions the framework seeks answers to are: who is living in poverty and how poverty looks in these dimensions, but we also ask why this situation came about when we analyse the development context, including political and institutional, economic and social, peace and conflict, and environmental aspects.

These elements – beyond the control of the individual– form poverty traps. One can say that the dimensions define our understanding of what multidimensional poverty is, while the different contexts provide an analytical framework for understanding the underlying constraints that keep people in poverty.

Who is considered poor in this framework?

According to Sida, a person living in poverty is resource-poor and poor in one or several other dimensions. So, we take resource poverty as a starting point, but enlarge the definition to the other dimensions. We think that resources are tightly connected to the other dimensions of poverty that together form the situations that keep people in poverty.

I think the previous approach focusing only on the resource dimension is possibly where we got lost in the first place, and why 10% of the world population is still living in income poverty. I think it’s because we haven’t seen the other interconnected dimensions and binding constraints that people living in poverty are facing.

How is this framework operationalised in the field?

It’s important to highlight that this framework serves the purpose of looking at different contexts. Within these contexts we can define who is poorer than the others. As we are working in very different countries, we are aware that the situation in Colombia is nowhere near the situation in Mozambique.

The framework also provides a tool for having a dialogue with partners and other stakeholders at the country level. Different countries have different definitions of poverty; this is our way of analysing and understanding multidimensional poverty, but we do not impose it on others. Instead, we would like to have a discussion on how poverty manifests itself for different groups of people in order to find a common understanding of the current situation, identify priorities, and find pathways out of poverty.

To move from a conceptual framework into applied use in our operations, we launched a toolbox for poverty analysis in 2018 and the toolbox is currently being updated with accumulated experience from the field offices. The methodological guidance has since been updated in light of COVID-19. This toolbox has a banner: make the model work for you. The country teams are allowed to adjust the framework and make their own country variations depending on the country context.

We started with a few pilot countries and asked: how does the dialogue look in your country? What are the main issues? And what issues would you like to highlight? And we asked them to systematically look at all the dimensions, but they were able to prioritise depending on whether it was a conflict country or not, or how the situation looked. We have now gone from a few pilot countries into a mainstream implementation of this type of thinking. Almost all the country teams have done their first multidimensional poverty analysis, and many are updating their analysis given the ongoing changes during the global pandemic. The multidimensional poverty analysis (MDPA) framework has really helped us to keep our eye on the ball and all the time ask how the changes we see impact the different dimensions of poverty.

What are the advantages of working with this framework?

I think the main change and the point of doing this in the first place is that we at Sida have become stronger in responding to development challenges and in understanding why poverty still exists in this day and age of material overload and wellbeing.

The framework allows us to embrace complexity and build theories of change in order to break the silos and poverty traps that still exist. Even now in times of a global pandemic, the framework has been flexible enough to accommodate ongoing changes and help us analyse the different mechanisms through which the people living in poverty are affected.

As I mentioned before, even if you would only narrowly focus on one part of poverty, say monetary poverty, it is important to realise that the main reason why people are still trapped in monetary poverty may not lie in that domain. It could be that it is based on discrimination, it could be that there are limitations to their capabilities and seeing what is actually holding them back. I truly believe in people living in poverty and their agency. If they have the chance and opportunity to lift themselves out of poverty, they will do it.

Talking about COVID-19, many international organisations have estimated that millions of people could fall back into poverty due to the global pandemic. What are Sida’s response and plans to address this?

I think the global pandemic and all the changes following it really underscore the need for a multidimensional analysis of poverty. In a short period of time, the number of people living in extreme monetary poverty is expected to increase rapidly as many were previously only barely above the poverty line and experienced several other deprivations making them vulnerable to poverty when a crisis hit. This makes it all the more important to understand the overlapping deprivations and structural constraints that push people into poverty.

We have adjusted our MDPA guidance to analyse changes that are specific to the current situation, but we have also noticed that many of the problems we see now are not really new but were weaknesses we could identify from previous MDPA analyses. It is almost as if COVID-19 is working as a magnifying glass emphasising the structural weaknesses that need to be better understood to sustainably reduce poverty.

In more concrete terms, Sida has been restructuring our development financing in light of our understanding of how COVID-19 impacts people living in poverty including the ‘new poor’ that risk falling into poverty, and allowing our partners to flexibly adjust to the needs on site. We have contacted all our partners asking what changes they see in the context they work in as the situation varies greatly.

In more concrete terms, Sida has been restructuring our development financing in light of our understanding of how COVID-19 impacts people living in poverty including the ‘new poor’ that risk falling into poverty, and allowing our partners to flexibly adjust to the needs on site. We have contacted all our partners asking what changes they see in the context they work in as the situation varies greatly.

As Sida’s preferred modality is to give core support, we have often been able to adjust the activities within our existing programmes and with our partners to better fit the current needs. For instance, a programme working with journalists to promote freedom of speech could quickly mobilise media to spread correct information about hand washing and other preventive measures.

In addition to changes within programmes, Sida has also increased support to humanitarian efforts and responded to urgent calls of support. Even though the Swedish economy has been hit by the economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, the government is committed to its goal to allocate one percent of GNI in development aid and Sida’s budget is expected to increase slightly for next year.

More info on Sida Poverty Toolbox.

This article was published in Dimensions 11