Search

Child MPI for Better Design and Implementation of Policies in Panama

In September of 2018, Panama launched its Multidimensional Poverty Index for boys, girls and adolescents as a complement to the national MPI launched the previous year. It was the first official MPI for that specific age range in Latin America. We discussed this index with Michelle Muschett, Panama’s former Minister of Social Development.

Considering that Panama already had a national Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), why was the decision made to create one to specifically measure poverty in boys, girls and adolescents?

Analysis of the results of the first calculations of the national MPI in Panama showed that 48% of people living in multidimensional poverty were under the age of 18. Based on the premise that boys, girls and adolescents have different needs, and that the deprivations affecting them have deeper and longer-lasting consequences than for adults, and the urgency of addressing them, the government of Panama saw the need to create a version of the MPI focused on this group. It is the most vulnerable group in the country and the goal was to foster better design and implementation of policies that are aimed at ensuring their well-being and full development.

What was the nature of the discussion at the technical and political level? What difficulties did you face in implementing the MPI for boys, girls and adolescents?

The Social Cabinet, the advisory body of the Cabinet Council, played an indispensable role in the development of the tool, serving as a space for them to articulate social policy with a comprehensive vision to encourage sustainable and inclusive development.

Government officials held comprehensive discussions about the national-level, political decisions needed to build the tool. These were informed by a technical team which comprised the Ministry of Social Development, Ministry of Economy and Finance and the National Institute of Statistics and Census.

The most intense discussions centred on gathering information related to the nutrition indicators and the final structure and dimensions of those indicators. After consultations and recommendations from our technical team and early childhood experts, we were able to reach consensus on a structure that was in line with a human rights vision and on the actions needed to gather the necessary data to calculate the indicators on nutrition and food security for this MPI.

One significant challenge was building the indicators while taking into consideration the differences among childhood age groups. These vary depending upon the indicator being measured due to the particularities of each of these groups.

The evidence indicates that investment in children can mean substantial savings for countries as it reduces the need for future spending in health, education and social assistance.

What were your main findings?

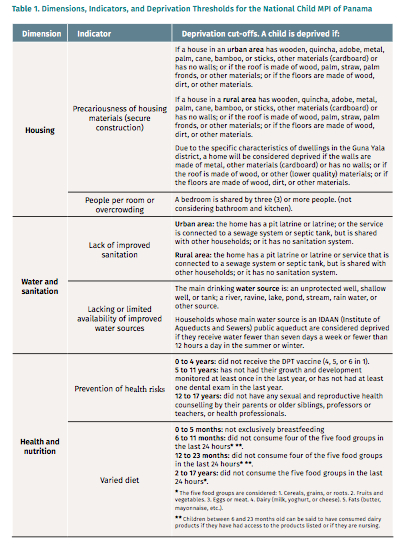

The national Child MPI (see table 1) is higher than the national MPI, with 32.8% and 19% of people multidimensionally poor, respectively. Similarly, the national Child MPI shows a higher intensity of poverty than the national MPI as boys, girls and adolescents, who are multidimensionally poor, suffer more deprivations simultaneously.

The dimensions with the greatest impact on multidimensional poverty for children in Panama are access to education and information (21.4%) and housing and environment (20.6%). In turn, the indicators that most impact poverty in this group are care, childhood activities and recreation, followed by overcrowding, and education and early childhood stimulation.

How will this indicator be used in public policies?

A tool like the national Child MPI will be key in designing and formulating public policies, since it helps to identify areas where this group’s needs are the greatest. This means we can approach them with a clearer understanding of the causes of these issues and focus our efforts on the territories and subgroups within the under-18 population.

In addition to the priorities established by each administration regarding the national Child MPI results, a policy bureau for boys, girls and adolescents will be established with the participation of various sectors of society. It will be based in a university and the goal will be to analyse information in depth and formulate public policy recommendations.

What would you recommend to other countries that have the objective of eliminating child poverty?

First and foremost, this should undeniably be a top priority in all countries. Policies aimed at eradicating child poverty should have a strong focus on early childhood, while not forgetting the adolescent population. At the same time, it is critical to work in a coordinated way with different sectors of society to comprehensively address the most urgent needs of children and adolescents.

The evidence indicates that investment in children can mean substantial savings for countries as it reduces the need for future spending in health, education and social assistance. Furthermore, there is a return on investment in children as it can act as a catalyst for economic and social development by facilitating the creation of productive human capital while ending cycles of poverty. Accordingly, the actions that we take –or do not take– today, with respect to childhood and adolescence, will have a decisive impact on our ability to honour our commitment to the 2030 Agenda.

Original in Spanish. Translated by Kristin Fisher.

This article was published in Dimensions 7.